I didn’t know Lyra as well as a lot of people – I wasn’t a close friend or even a close associate.

However, in these days of constant online interaction I did feel a connection to her as someone I corresponded with on and off since early 2014. It was late February 2014 in fact when my friend Prof. Graham Walker sent me an email saying that he had been talking to a journalist called Lyra McKee who was ‘keen to make contact’ and seemed to ‘know a bit about [John] McKeague and other figures from the 60s/70s’. I’d been aware of Lyra since the summer of 2013 when her project on the Robert Bradford story was announced on Slugger O’Toole.

I have to admit that I was a bit guarded, and wasn’t sure whether to make contact – I had, in February/March 2014, just made a connection with someone who had known John McKeague well [he has since become a close friend] and I didn’t want to jeopardise that link as I was focused on my own work, having just signed off on the contract for my book.

In the event, Lyra emailed me and we emailed back and forth, trying to find a date to meet up for a drink and a chat. Something I have often bemoaned and am indeed guilty of, is that we rely so much on online interaction nowadays, it can be a substitute [or at least feel like an adequate substitute] for real, human contact.

So developed an online link where myself and Lyra could go for months, even years, without contact and then we would have an interaction on Twitter or whatever.

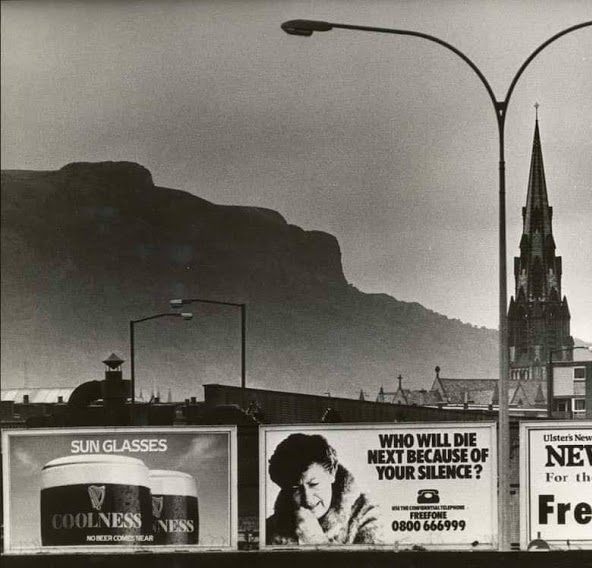

I felt an affinity towards Lyra as she came from the same neck of the woods as I had spent my early years. My parents had moved from the Deerpark Road to the Cliftonville in 1975. Talk about jumping from the frying-pan into the fire. When they had a bit more money, they moved from the Cliftonville to further up the Antrim Road in 1986. They wanted to protect myself and my brother from the worst of the violence.

I therefore enjoyed a relatively sheltered upbringing in terms of the Troubles.

The worst thing that happened to us was that our windows were blown in on a few of the many occasions that the Provos decided to bomb the Lansdowne Hotel, a street away from us.

A boy in the year above me in primary school who lived two streets away witnessed his father being shot dead during Sunday dinner in February 1989. I still remember John Finucane – though he may not remember me – coming around to play football in our back garden as he was friendly with a neighbour. He seemed tense, wired-up. He was [probably] 9 – I was 8. We just played football, and I can’t remember if we even exchanged words. I couldn’t appreciate the gravity of what had happened, but I knew this was something beyond the normal. Young boys can interact with each other pretty easily without words when there’s a football thrown into the mix. I think – and I might be wrong here as my memories are hazy – that John ended up going to stay in Australia for a period; perhaps with family? No wonder. What a traumatic thing for a young boy to have to see.

People look at that part of north Belfast and think that because people are comfortable enough then the Troubles probably didn’t affect them. Its true that we were generally safe from the worst excesses of the violence, but there were still the hotel bombings, the killing of Pat Finucane, the persistent attempts by the Provos to blow up Judge Eoin Higgins in his home, the 1996 killing of John Molloy [I still remember the RUC combing our front garden trying to find the murder weapon] and years later the brutal murder of young Thomas Devlin.

North Belfast has always had a shadow over it. I firmly believe that if you’re thoughtful enough to appreciate the blood that was spilled on its streets and the effect that the 1970s and 1980s had on the people who lived across the neighbourhoods there then you’ll always have feelings about the Troubles at the back of your head, at the very least.

I know that Lyra felt the same. She was ten years younger than me, so I assume she was born in 1990. While I became obsessed with understanding the violence of the past as it had affected north Belfast, I believe that Lyra had a similar obsession with understanding the social detritus that the bloodshed on the streets of north Belfast had dumped onto her generation – the ‘ceasfire babies’ as she referred to them as.

As I watched Lyra’s self-made career take off, I felt admiration that this young girl had such a deep desire for knowledge and a drive to succeed. She was the first person I heard about using crowdfunding. I don’t think I’d ever heard of crowdfunding before that. Instead of complaining about the obstacles in front of her, she defiantly challenged them and problem-solved to the extent that she carved out a deserved reputation as an incisive investigative journalist.

When my sister-in-law moved back to Belfast with her young family last year after living in London for around 16 years, Lyra was one of the first people to try and assuage Seaneen’s anxieties and doubts about returning to Northern Ireland. She made the case that this was a good place to live. Similar stories about her emotional generosity have emerged in the past 24 hours.

Over the past year we had been in contact again more regularly. I had been itching to hear how her book on the last days of Robert Bradford was progressing. She sent me the manuscript and was keen to see what I thought of it. I was particularly interested in her upcoming book ‘The Lost Boys’ as I had read in the newspaper archives about the young men who went missing during the Troubles without a trace.

Before Christmas there was an announcement that due to the lack of an appropriate Minister, all FOIA requests were being temporarily suspended. I took to Twitter to voice my frustration that it now seemed that I would never get access to internee files relating to deceased loyalists such as Lennie Murphy and Ken Gibson to name but a few. These were files I had already been messed around on for nearly 5 years. Lyra responded and talked of the heartbreak that the decision had caused for families of Troubles victims she was working with. Her humane, caring take on the situation made me feel truly humbled and almost ashamed. She was trying to dig for the truth in a way that would settle people’s worst anxieties. I was probably looking for slightly more ephemeral information.

After Christmas I asked Lyra would she be up for chatting for the ‘Hidden Histories’ podcast that I had started in October. She immediately got back in that infectiously enthusiastic manner and said ‘Yes, absolutely’. She had to check with Faber with regards to how much she could talk about in relation to ‘The Lost Boys’. To be honest, I was just looking forward to having a yarn on the record with another north Belfast native who was also consumed by a desire to understand this little part of the island of Ireland which we call home. As usual, life got in the way for us both and for two months we left it.

I emailed Lyra on Wednesday and said ‘Look, I haven’t forgotten about our arrangement, but I’m trying to relaunch the Hidden Histories as a strand of a larger project I’ve envisaged – would you be up for doing the interview soon?’ As ever, she came back immediately. She was buzzing that the cover art for her Robert Bradford book was being finalised and suggested that as the release date was coming down the line, we might do the podcast to coincide with that. As in a lot of her emails to me she called me ‘Sir’ – not in a deferential way, just in that nice way she seemed to have about her.

I’d been looking at the June 1973 killing of young Sammy McCleave – one of those Troubles murders that had always stuck with me since I first read about it. The strange circumstances that followed it, including the death [murder?] of his brother in 1979 intrigued me. Sammy’s brother was gay and it was often insinuated that he had been the victim of a so-called ‘queer-bashing’. Nothing in the deaths of McCleave, his brother or the young man who died in an apparent ‘revenge’ attack in the months after June 1973 ever sat right in my head.

I asked Lyra on Wednesday had she ever heard of the Sammy McCleave case?

‘No’.

In my head, it was an ideal project for Lyra at some stage in the future. I sent her newspaper clippings relating to the deaths.

‘OMG, you’re right. That is really, really odd’.

I was secretly hoping that Lyra would allow me to collaborate with her on this in the future. She had the wherewithal to deal with difficult and complex subjects like these killings. I knew she could weave a captivating and humane narrative around the events.

Sadly, I’ll never know whether we could have worked together.

She was murdered a day later by idiotic dogmatists with nothing to offer society.

Before I went to bed on Thursday night I continued reading Patrick Radden Keefe’s ‘Say Nothing’. In Lyra’s book on Robert Bradford, she described Radden Keefe’s early work as having influenced her approach to that project.

As I drifted off to sleep, I put ‘Say Nothing’ on the bedside table.

At 12.30 a.m. I awoke and not being able to get back to sleep I continued reading.

A while later I lifted my phone and logged on to Twitter. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing/hearing/reading.

Lyra was an immensely skilled journalist with a lot of experience under her belt, but she was also a very young woman. Only 29 years old. The recent past in Northern Ireland will remain that bit more clouded without Lyra’s contribution to overturning stones and shining a light on the darkest corners.

My heartfelt and sincere sympathies go out to Lyra’s mother, partner, family and close friends. I hope that the tributes paid to her today and which will continue to be paid to her over the coming days, weeks and years will provide some sort of comfort to them.

“When they had a bit more money, they moved from the Cliftonville to further up the Antrim Road in 1986. They wanted to protect myself and my brother from the worst of the violence.

I therefore enjoyed a relatively sheltered upbringing in terms of the Troubles”.

My father was very proud of the fact that long before 1986 (after an attempt on his life) he had bought property in an enclave on the north belfast/newtownabbey boundary that protected his children

“living here, you wouldn’t know there was anything going on ” he used to say. He was quite right

You wouldn’t have.

There was absolutely no need for us children to feel involved in anything.

The News was switched off at home so we didn’t hear anything.

We had our music/dance/speech and drama/riding lessons

There was a local consensus in the enclave on the WWII-like blackouts in our area so you couldn’t see that our houses with their large unlighted gardens/driveways even existed . . .

Until we put our noses out of the door/enclave and drove/walked/ bussed our way down the Antrim Road . .