In Homage to Catalonia, his firsthand account of the Spanish Civil War, George Orwell stated that ‘One of the most horrible features of war is that all the war-propaganda, all the screaming and lies and hatred, comes invariably from people who are not fighting.’ While this has been the case in numerous conflicts there are other forms of ‘war propaganda’ where the protagonists – or at least those closely sympathetic to their cause – are an essential component in the message, whether it is in print or another medium. This has been particularly evident in the Irish conflict, where since 1906 An Phoblacht (translated into English as The Republic) has been the propaganda newspaper of republicans in one guise or another until 1970 when the post-split Provisional IRA in the Republic of Ireland under the leadership of Ruaírí O’Bradaigh wrested ‘legitimacy’ of the title for their own cause. An Phoblacht’s position as the authoritative vessel for Provo propaganda was further strengthened by a merger with the Northern publication Republican News in 1979. Throughout the 1970s and beyond An Phoblacht outlined the operations of the PIRA and gave coverage to the military and political thinking of leading Provisional leaders, often under pseudonyms. Scores of other smaller republican propaganda literature emerged throughout the twentieth century, with the so-called ‘dissident’ groupings printing their own narrative publications.

While the past decade or two has witnessed an emerging scholarship on loyalist paramilitarism, scant attention has been paid to the propaganda and print – the ‘underground press’ and attendant culture – of the paramilitary organisations. As an historian it has often baffled me that these sources aren’t more widely exploited in historical accounts of this aspect of the Troubles.

Historically loyalists had no widespread experience of incarceration for their beliefs or actions, meaning that a culture of resistance with the concomitant propaganda did not exist to the same extent as it had done within militant republican culture. However, with the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force in 1965 and the organisation’s killing of three people in 1966, loyalist paramilitaries including Gusty Spence were jailed. Soon after epistles and verses celebrating the loyalist cause and bemoaning the incarceration of ‘loyal men’ who had ‘taken up arms for Ulster’ began to emerge from Crumlin Road gaol. These eventually formed the basis for songbooks and other paraphernalia which was sold at stalls in the Shankill, east Belfast and other Protestant working-class districts to raise money for loyalist prisoners’ welfare.

Through such sources we begin to see the evolution of the various cultures and narratives of loyalist paramilitarism as expressed through the lens of these and other documentary sources which grew exponentially after 1970 to include news-sheets, songs, magazines, communiques, prison journals, prison handicrafts and letters to and from prisoners who were incarcerated throughout the course of the Troubles. These sources provide a stark insight into the manner in which loyalist paramilitaries sought to depict themselves during the years of conflict and thus how they influenced perceptions of the UVF, Red Hand Commando, Ulster Defence Association/Ulster Freedom Fighters and other smaller loyalist organisations both within their own communities and further afield.

In delving into the culture of the underground loyalist press during the Troubles a complex and often fascinating web of individuals, gossip and internal squabbles emerges. There are inputs from cartoonists, magazine editors, musicians and singers, articles by propaganda writers and statements from prisoners’ families. Many of these supporters are what the late ‘Plum’ Smith, a former RHC prisoner, referred to as the ‘hidden battalions’ in his 2014 prison memoir. Their stories have hitherto been untold in the public domain, with a few notable exceptions, but their role in the history of the conflict in Northern Ireland has been crucial and demands proper exploration. The underground press provides a window into this often disorientating and seemingly impenentrable world.

The early 1970s bore witness to a steady emergence and then dramatic proliferation of loyalist paramilitary, political and community groupings and initiatives. While republicanism is infamous for its historical splits and feuds, the fracturing of Protestant working-class communities at the beginning of the most recent Irish conflict was dramatic with loyalties divided and often refracted through the creation of a number of paramilitary organisations. Many of these organisations came to be bitter rivals during periods of inter-communal turmoil. The formation and development of the various factions within loyalism led to the production and rapid growth of a loyalist underground press comprising news-sheets and bulletins. Some of these are still in production, albeit under different guises, whereas others imploded after just a handful of editions.

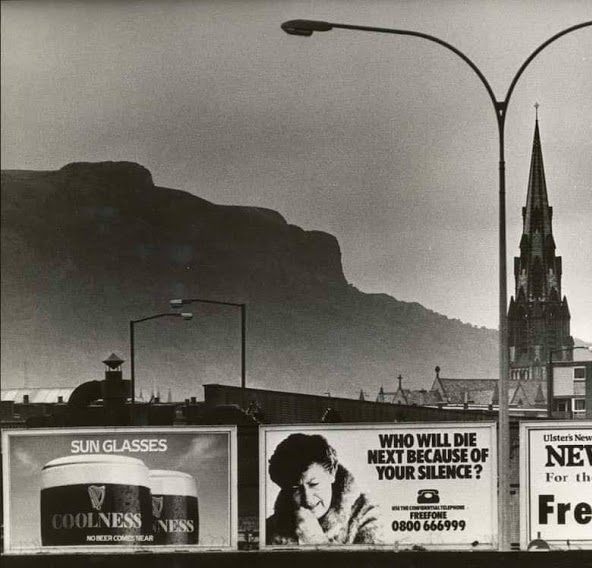

In the age of social media, where rumours and conjecture are updated second by second on the internet it might seem almost quaint to consider a world where people printed their own news sources within relatively small communities. These were, after all, short-lived news-sheets and journals as well other fleeting mediums for paramilitary propaganda, but it must be remembered that in the 1970s particularly these were the secretive and arcane mediums through which often fascinating insights into an emerging subcultural world could be accessed. The CAIN resource website states that much of the ephemera produced relating to the conflict in Northern Ireland, ‘…often provides insights that are perhaps not available in the more formal materials produced by political groupings and which are to be found in official archives and records.’

This series of short articles highlights some of my most interesting discoveries while researching, collecting and reading these historical artifacts.

Part one looks at the profiles of loyalist prisoners which were published in the early 1970s and the narratives of resistance that were constructed around these individuals and the reason for their incarceration.

The Ulster Loyalist was published for around two years between 1973 and 1975 by the UDA in Belfast. In a fashion similar to The Orange Cross at the time the paper published pen pictures of various UDA prisoners accompanied by a brief hagiography around the nature of their incarceration and information relating to the individual’s family background. One that immediately caught my attention was that of a young Shankill loyalist named Joe McAllister.

As a 19-year-old McAllister had been convicted of the brutal murder of Catholic publican Benny Moane in May 1972. Along with ‘Joker’ Andrews, whose father had been killed in the PIRA bombing of the Four Step Inn in September 1971, McAllister and some associates abducted Moane after overhearing that he was a Catholic. Moane had found himself in a Shankill bar on the day of the funeral of John Pedlow, a Protestant teenager who had been shot dead by the PIRA during a gun battle at Springmartin on 14 May. He was there for work; he was a drink salesman and regularly visited pubs across Belfast as part of his job. Feeling that he may cause upset to the mourners with his presence in the pub Moane told the owner that he would be leaving. This fundamental act of decency inadvertently sealed his fate in what was a febrile and increasingly paranoid city.

McAllister and the other UDA men hustled Moane out of the pub and shoved him into a car which was driven to the Knockagh Monument, a First World War memorial high in the hills above Greenisland which provides a dramatic view across Belfast Lough.

When the men arrived on the hill they plundered Moane’s drink samples and told concerned visitors to the beauty spot that they had captured an “IRA man” and were subjecting him to an interrogation. This was a gross lie and one can only wonder how fearful and helpless any innocents who encountered the unfolding scene felt. The episode is a jarring vignette of the brutality of the accelerating Troubles clashing with the attempts by the majority of people in Northern Ireland to live normal lives.

McAllister must have had doubts about what they had done, or at least the validity of the claims that were being made about Moane being a member of the IRA. Although he was young, McAllister was no subordinate, and his reaction in the immediate aftermath of the murder is telling. It was reported by Dillon and Lehane in their 1973 book Political Murder in Northern Ireland:

McAllister said he told Moane to lie face downward on the ground and it was at this point that Moane said: ‘Ah, no boys.’ When Moane refused, McAllister shot him through the forehead and then, on Swain’s orders, shot him twice when he fell to the ground. Swain then told McAllister to empty the rest of the rounds into Moane’s body. But McAllister turned to Swain and said: ‘If I have to fire this revolver again it will be into your fat mouth.’ He is also alleged to have told police that if he ever discovered the man who ‘spread the lie that Moane was an IRA man’, he would shoot them.

In the Ulster Loyalist article on Joe McAllister the author stated ‘When one seeks information to do a profile, the bits and pieces that make it up come easily, or they did until I came to Joe. This man’s life has blended so well into the background of everyday life that I can only assume he is typical of the thousands of ‘ordinary’ people who live out their lives in Ulster today.’

In 1987, fourteen years after McAllister’s sentencing and imprisonment for the murder of Benny Moane, his family spoke to Jim Campbell of the Sunday World complaining that he hadn’t been released. In the mid-1980s McAllister had fallen in love with a Ballymoney woman named Helen Peden who had started writing to him as a pen pal. ‘He was only 19 when this terrible thing happened and he says he’s regretted it ever since’ Peden told Campbell. The family claimed that they didn’t condone what Joe McAllister had done or underestimate the sorrow and heartache he had caused to the Moane family, his sister Betty stating ‘Our hearts go out to them. And Joe has written letters from the jail telling how never a day passes but [sic]he doesn’t wish the poor man was still alive and with his family.’

A family friend who spoke to Campbell claimed that in the days before Moane had been murdered he was one of five Protestants who had been kidnapped by the IRA at a roadblock in Andersonstown and taken away to be interrogated. The family friend and another man escaped and raised the alarm, claiming that the army flooded Andersonstown and freed the three Protestant men. ‘But by that time rumours that the Protestants had been tortured and killed swept the Shankill Road and Bernie Moane was shot.’

As an aside it is interesting to note that Joe McAllister’s younger brother eschewed the UDA and joined the UVF, eventually coming under the command of Lenny Murphy. Sam McAllister – ‘Big Sam’ – would gain infamy as a prominent member of the Butcher gang which was convicted of a series of murders that were the result of a sustained campaign of sectarian bloodshed and intra-loyalist feuding from 1975-77.

__

Thanks Eddie. Had that sitting for months so thought I’d put it out for people.